Telling her story: Women share their experiences of obstetric fistula

Obstetric fistula is one of the most dangerous and most misunderstood birth injuries. Every year, 50,000 to 100,000 women develop this devastating childbirth injury.

Obstetric fistula occurs when a woman experiences prolonged labor – often for several days – and is unable to access emergency delivery care. The baby cuts off blood flow to tissues in the mother’s pelvis. After the baby has been delivered, the dead tissue falls away, leaving a hole in the birth canal that can leak urine or feces.

Tragically, even after a difficult delivery, very few fistula survivors are able to bring their baby home. The injury is closely associated with stillbirth, with over 90 percent of survivors delivering a stillborn.

While obstetric fistula is a debilitating injury, it is easily prevented with proper maternal health care. We work all over the world to end obstetric fistula and make the world a safer place for moms and their babies.

Keep reading to hear from five fistula survivors and the impact the injury has had on their lives:

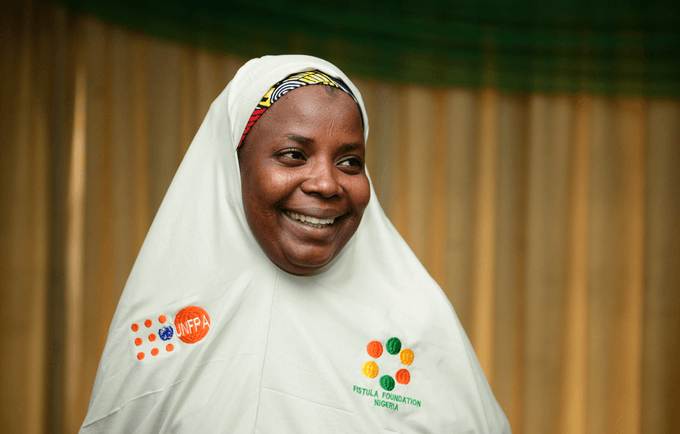

Hafsatu in Nigeria

“I got married at age 14 and was in labor for 3 days” Hafsatu told us after her fistula repair surgery. She was too young to be pregnant and with no midwife present, she was more susceptible to pregnancy and childbirth complications. Hafsatu developed an obstetric fistula — and she lived with the condition for 20 years. “I remember how lonely I was, I did not participate in feasts or visit relatives, and when my first surgery failed, then the 2nd, the 3rd, the 4th … I thought I was condemned to spend the rest of my life in shame but thank God I was wrong,” she said.

Hafsatu’s experience is not uncommon in her native northern Nigeria. 1 in 4 girls in the region becomes a child bride and, overall, Nigeria has the number of fistula survivors in the world. Hafsatu received care at a UNFPA-supported clinic, and today, she has reunited with her husband and is able to socialize freely with her family and community. She has even started her own business.

Razia in Pakistan

Razia grew up in the Punjab region of Pakistan, and by all accounts, she had a hard life.

Her family held traditional attitudes toward women, leaving Razia without an education and married by her 13th birthday. She became pregnant soon after, but, tragically, her husband died 6 months into her pregnancy. Razia gave birth alone, except for a traditional birth attendant who was unable to care for her complications. She was in labor for 4 days, before finally giving birth to a stillborn daughter.

In the process, Razia developed multiple fistulas, which she lived with for years, saying “People would either avoid me or just make fun of me. I never felt clean.”

She was finally able to receive care at a UNFPA clinic. Razia had to have multiple surgeries over 6 years, due to the complexity of her injuries, but now, she has her life back. She has married, adopted one child, and much to her surprise, was able to conceive and give birth to a healthy baby girl.

As tragic as Razia’s story is, it is not uncommon.

Adolescent pregnancy is incredibly dangerous and is the biggest killer of girls 15-19 in the world. Girls’ pelvises, even if they’ve gone through puberty, are not developed enough to deliver a child. In too many cases likes Razia’s, this can result in obstetric fistula, other birth injuries, or death.

Keflene in Tanzania

“I started attending prenatal clinics as soon as I realized I was pregnant, and continued throughout my entire term.”

Sadly, even if you follow every guideline, like Keflene, obstetric fistulas still happen.

Kefelene lives in a rural and impoverished part of Tanzania, which made it impossible for her to go to a hospital when she went into labor. Instead, she had a traditional birth attendant, who was unable to help her through three days of labor. Eventually, Keflene’s baby was stillborn and Keflene spent over a month in the hospital recovering from complications from the delivery.

UNFPA-supported research found that transportation costs were a major factor for Tanzanian women when they were deciding whether to give birth at home or at a hospital. Just under two-thirds of women have a skilled birth attendant with them during delivery.

Luckily, Keflene was able to receive fistula repair surgery and is now an advocate for other women living with fistula.

Ager in Ethiopia

Ager grew up in a rural farming community in Ethiopia. When she was 12 years old, her family gave her away in an arranged marriage to a man many years her senior. She had five babies at home and with each, Ager spent a day or more in labor before having a stillborn. When it came time to deliver her sixth baby, Ager against spent 24 hours giving birth at home before her family took her to a clinic for care. There, she received emergency care — but it was still too late. Ager lost her sixth baby, had to have a hysterectomy, and developed an obstetric fistula. She remembers feeling like, “I wished I died as my babies. I was in so much distress and shame.”

Ager eventually got referred to a UNFPA-supported fistula treatment center where she met women just like her. After multiple surgeries and a long recovery, she finally feels hopeful again. “I did not believe I would be cured, but thanks to God, I feel like I have been reborn. I have no words to thank the doctors, nurses, and everyone who supports this godly work. Now, I am eager to mix with my family as a woman with full dignity,” she told us.

Margret in Malawi

in that situation, you try almost everything,” she said. © UNFPA Malawi/

Henry Chimbali

Margret lived with a fistula for 13 years before finding help.

She became pregnant at 14 and suffered a hard delivery, ultimately resulting in her condition and a stillbirth.

Like many women who experience fistula, she faced chronic health conditions. Recurring infections, depression, and anxiety are all common to these women. Margret’s husband stayed with her, but many women’s husbands or families abandon them after they develop the fistula, further isolating them when they need support most.

Margret said, “I never enjoyed being a woman since I had this condition. It was tough to live.”

Margret was able to receive fistula repair surgery at a UNFPA-supported event. Now, she had two children and is an advocate for other women living with fistula.

Nagat in Yemen

Nagat is a midwife in Yemen. She knows exactly how dangerous fistula can be and how to prevent it from ever happening in the first place.

But during her first pregnancy, she lacked the power to make her own reproductive health choices. Her husband’s family viewed the hospital as a “luxury” and as Nagat explains, “I stayed for four days suffering from pain trying to give birth, but in vain. My body was exhausted, and I was physically and psychologically worn-out.”

Eventually, Nagat was able to have a Caesarean section delivery, and miraculously, her baby survived! Soon after, however, she realized she had an obstetric fistula. Unable to resume her household duties, her husband left her and took their child with him.

After 7 months, Nagat and her family were able to save enough money to transport her to a clinic that performs repair surgeries for free. Now, Nagat misses her daughter terribly, but is able to ensure other women receive the care they need and don’t have to experience fistula like she did.

Ending Obstetric Fistula for Good

Obstetric fistula turns women’s lives into a living nightmare, constantly worrying if they’re going to be the subject of ridicule or left abandoned because of something they cannot control. Fistula is easily preventable by a timely Caesarean section, and, in the parts of the world where women have adequate access to care, the fistula has essentially eliminated. But, for 2 million of the world’s most marginalized women – women who live in poverty, with disabilities, lack agency over their lives, were child brides or who have experienced FGM – obstetric fistula is another barrier to a safe and healthy life.

UNFPA is working to eliminate obstetric fistula by 2030 through clinics that provide free fistula repair surgery, by training and supplying midwives who are essential to ensuring that mothers have a safe delivery, and by training survivors of fistula on how to become advocates in their communities.